Cold Weather Concreting_Common Problems and Effective Solutions

As the cold season approaches and temperatures decline, significant impacts are imposed on the daily activities of construction workers—particularly when concrete placement is involved. Freshly placed concrete is highly vulnerable to freezing temperatures, rain, snow, or freezing rain, both before and after setting. Therefore, in cold weather conditions, monitoring and controlling concrete temperature becomes critically important.

Cold-weather concreting is a complex and sensitive engineering process that, if not executed according to technical principles, can lead to irreversible damage to the strength and durability of concrete structures. This comprehensive guide thoroughly examines the key challenges caused by low temperatures, including hydration توقف and freeze-related damage, and emphasizes the vital role of site equipment such as concrete formwork systems and scaffolding in protecting concrete. Serving as a practical reference for construction professionals, this guide aims to ensure safety, quality, and long-term performance of concrete projects.

What Is Cold-Weather Concreting?

The term *cold weather concreting* is used when, for three consecutive days, environmental conditions meet the following criteria:

- The outdoor air temperature is below 40°F (4°C).

- The air temperature remains below 50°F (10°C) for more than 12 hours per day.

Under these conditions, the setting and hardening process of concrete slows significantly, and if appropriate precautions are not taken, the ultimate strength and durability of the concrete may be adversely affected.

Why Does Cold-Weather Concreting Require a Scientific Approach?

Concrete, as one of the most fundamental construction materials, is used throughout the year under varying climatic conditions. While concreting under moderate conditions is relatively standardized, the onset of colder seasons introduces unique challenges for engineers and contractors. Low ambient temperatures directly affect the chemical and physical processes of fresh concrete and can significantly reduce its strength, durability, and surface quality.

In conditions where the setting and hardening processes are slowed or halted, the risk of freezing water within the concrete pores increases. This phenomenon causes internal and often invisible damage that can severely compromise concrete performance. Consequently, cold-weather concreting goes beyond a simple execution task and becomes a fully engineered process requiring precise planning and technical expertise. This report serves as a comprehensive reference, providing practical and standards-based solutions while highlighting the critical role of specialized equipment in ensuring project success.

Why Is Compliance with Cold-Weather Concreting Principles Essential?

During concrete placement, concrete temperature is one of the key factors in ensuring quality and ultimate strength. Temperature measurements are commonly taken to verify compliance with allowable temperature ranges specified in standards.

- Typically, the temperature of concrete at placement should range between 10°C and 32°C. However, acceptable limits vary depending on the size of the concrete member and ambient conditions, as defined in ACI 301 and ACI 207.

- The temperature of concrete during placement directly influences its temperature during hydration (setting and hardening).

- By carefully monitoring temperature variations during concrete curing, engineers can ensure that the structure achieves the desired strength, quality, and durability.

Failure to comply with cold-weather concreting principles can lead to serious problems and even structural damage, including:

- Freezing of concrete during early setting stages,

- Failure to achieve the required compressive strength,

- Rapid and sudden temperature fluctuations,

- Insufficient protection and reduced durability of the structure,

- Improper execution of concrete curing.

Therefore, strict adherence to guidelines and precise temperature control throughout all stages of cold-weather concreting is vital to ensure structural safety and service life.

5 Key Measures for Controlling Concrete Temperature in Cold Weather

- Use of internal electric heating:

This method involves embedding insulated electrical cables or resistance elements within the concrete to generate sufficient heat and prevent freezing. - Optimization of concrete mix design:

Utilizing low-heat cement, supplementary cementitious materials such as fly ash, limestone, or slag, and reducing the water-to-cementitious materials ratio are effective strategies for retaining heat in cold-weather concrete. - Use of insulation:

Applying insulating blankets or insulated formwork helps retain heat generated by hydration and controls temperature gradients between the concrete core and surface. - Cooling concrete before placement:

Cold water, crushed ice, or liquid nitrogen may be used to reduce concrete temperature prior to placement in order to prevent excessive thermal reactions. - Cooling concrete after placement:

Non-corrosive cooling pipes are installed within the formwork before concreting, allowing cold water to circulate after placement and dissipate excess heat.

In-Situ Concrete Execution in Cold Weather

When working with fresh concrete, its temperature must remain above freezing or no more than 10°F (approximately –12°C) below the minimum required temperature.

According to ACI 306, concrete temperature must be maintained at a minimum of 40°F (above 5°C) for at least 48 hours.

The minimum compressive strength required before freezing is 3.5 MPa (500 psi). If concrete freezes before attaining this strength, the expansion of water during freezing causes cracking and internal damage.

To prevent freeze damage, all concrete surfaces must be protected during the first 24 hours after placement.

Additionally, when removing ice, the volume of ice present must not exceed 75% of the total mixing water, in accordance with NPCA guidelines.

7 Common Mistakes in Cold-Weather Concreting

To avoid structural issues and project delays, it is essential to be aware of common cold-weather concreting mistakes. The following seven errors should be carefully avoided:

1. Placing Concrete on Frozen Ground

The substrate plays a critical role in concrete curing conditions. Concreting on frozen ground leads to settlement once the ice melts, resulting in cracking. Moreover, concrete in contact with cold ground cures more slowly at the bottom than at the surface, creating temperature gradients that weaken structural integrity.

2. Allowing Fresh Concrete to Freeze

- Concrete should be maintained at approximately 10°C to cure properly.

- Fresh concrete freezes at –4°C; therefore, it must be kept warm until sufficient compressive strength is achieved.

- Temperature sensors can be used to accurately monitor curing and ensure proper temperature control.

3. Using Cold Tools and Equipment

Keeping tools, formwork, and materials warm is just as important as maintaining concrete temperature. Cold formwork can adversely affect concrete in direct contact and disrupt setting and strength development, ultimately reducing slab performance.

4. Failure to Use Heating Equipment

- Concrete must remain at appropriate temperature levels to gain strength.

- If concrete temperature drops too low, curing completely stops.

- Portable heaters may be used to apply direct heat to the ground and concrete surface; however, improper heating can lead to structural weaknesses and must be carefully controlled.

5. Sealing Concrete in Extremely Cold Weather

- Concrete sealers enhance resistance against environmental and weather-related effects.

- For cold-weather applications, sealers specifically designed for harsh conditions must be used according to manufacturer recommendations.

- In general, sealing should not be performed at temperatures below 10°C, as material performance significantly degrades.

6. Misjudging Available Daylight Hours

- Daylight duration is shorter during colder months.

- Accurate scheduling is essential, as delays increase project risks.

- Daylight not only improves visibility but also contributes to warming the concreting environment.

- If concreting is unavoidable before sunrise or after sunset, heating and protective coverings must be used.

7. Failure to Use Real-Time Temperature Sensors

To properly evaluate the effectiveness of protective measures, continuous monitoring and logging of concrete temperature is essential.

Traditional systems such as wired thermocouples and data loggers present challenges in cold weather:

- Exposed wires are vulnerable to damage,

- Data loggers may malfunction at extremely low temperatures,

- Manual installation and data collection are time-consuming,

- Reading data beneath thermal blankets can be difficult.

For these reasons, wireless temperature sensors such as SmartRock have been developed to address these challenges.

These sensors are fully embedded within the concrete and require no physical connection to data loggers, eliminating:

- Exposed wires susceptible to damage,

- The need to locate sensors beneath thermal blankets,

- Errors and failures caused by cold temperatures or damaged wiring.

The Main Challenge of Concrete in Cold Weather

At low temperatures, the hydration reaction (the exothermic chemical process between cement and water that leads to setting and hardening of concrete) slows down significantly or may completely stop. This problem becomes more severe at subzero temperatures, where hydration is practically suspended.

Risk of Freezing

Freezing of pore water within concrete is one of the most serious threats in cold weather. Due to dissolved salts, the water inside fresh concrete freezes at approximately –1 to –2°C. This freezing is accompanied by a volumetric expansion of about 9%, generating severe hydrostatic pressure on the pore walls. If this pressure exceeds the tensile strength of fresh concrete, microscopic cracks develop and the internal structure of the concrete is damaged, resulting in loss of density and increased brittleness.

Permanent Consequences

Damage caused by freezing during the early hours of concrete setting is irreversible. Even with proper curing after a freezing event, the concrete will not reach its designed strength and durability and may lose up to 50% of its final strength. This reduction in strength is the result of irreversible microscopic damage to the internal concrete matrix.

Preventive Measures

The use of antifreeze admixtures, thermal insulation, or heating systems can effectively prevent freezing and strength reduction in concrete. The cost of these preventive measures is negligible compared to the expenses associated with repairing or reconstructing damaged structures and represents a sound investment in ensuring project safety and durability.

Signs of Freeze-Damaged Concrete

Detecting freeze-damaged concrete at early stages can be challenging; however, careful inspection can reveal several recognizable indicators, including:

- Surface scaling and flaking: One of the most common and critical signs of damage is surface peeling and separation of concrete layers. This deterioration can occur under very minor loads or even light pressure (such as finger pressure or shoe impact), indicating that the surface layers failed to develop sufficient strength.

- Softness and lack of setting: In thin concrete members, such as slabs cast over EPS blocks, the softness and lack of stiffness are easily noticeable by touch. Light pressure may reveal flexibility and incomplete hardening.

- Fine cracking: In thicker elements such as walls and columns, hairline or microcracks may appear. These cracks typically form due to internal stresses caused by ice expansion.

- Powdery texture: In cases of severe or prolonged damage, freeze-damaged concrete may exhibit extensive cracking and disintegrate into a powdery, sand-like material.

Requirements and Measures for Cold-Weather Concreting: Risk Management and Quality Assurance

Cold-weather concreting (when ambient air temperature falls below 5°C or is forecasted to do so) presents serious technical challenges, as hydration slows and the risk of water freezing within concrete increases. According to ACI 306R-16, cold weather refers to conditions where the air temperature is below 4°C or is expected to drop during the protection period.

The primary objectives include preventing early-age freezing, achieving sufficient strength for formwork removal, maintaining proper curing conditions for strength development, limiting rapid temperature fluctuations, and providing protection commensurate with the structural function. In Iran, the Iranian Concrete Code (ABA) emphasizes that concreting below 5°C is prohibited unless special protective measures are implemented, and fresh concrete must be protected against freezing to prevent strength and durability loss. This guide draws upon authoritative resources such as ACI standards and Persian technical references to address preparation, mixing, admixtures, and protection methods.

Preparation Phase: Detailed Planning and Risk Management Prior to Concreting

The success of cold-weather concreting is highly dependent on meticulous planning. This phase is the most critical step in risk reduction and includes reviewing weather forecasts for the coming days, particularly during the concrete protection period. Contractors must assess temperature, precipitation, and wind conditions and secure equipment such as digital thermometers, protective coverings (e.g., polyethylene sheets or thermal blankets), heating devices (portable or hydronic heaters), and insulation materials. ACI 306R recommends that planning account for temperature loss during transportation, which typically ranges between 11–28°C per hour.

Preparation of the Subgrade and Work Environment

Placing concrete on frozen, snowy, or wet surfaces is prohibited. Subgrades, formwork, and reinforcement must be cleaned of snow, ice, and water and thoroughly dried. Contact between fresh concrete and cold surfaces can cause localized freezing, reduced bond between concrete and steel, and an overall decrease in structural strength. ACI emphasizes that the subbase must be thawed and maintained above freezing.

Preheating reinforcing steel and metal formwork is essential, as metals are highly conductive and absorb heat from concrete. This heat loss can freeze surface concrete layers and halt hydration. Heating methods include steam spraying, controlled flame heating, or electric heaters to raise temperatures above freezing. Persian technical sources such as SabzSazeh recommend protecting aggregates with plastic or tarpaulin covers overnight to prevent freezing.

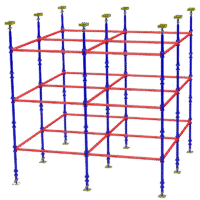

Selection and Preparation of Formwork and Scaffolding Systems

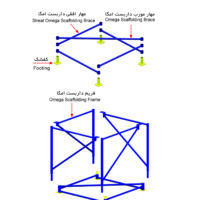

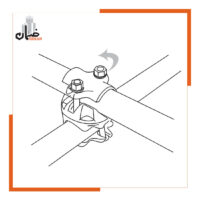

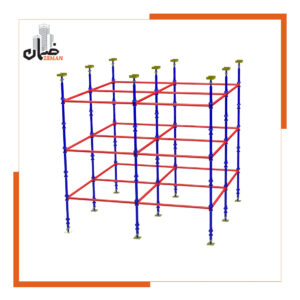

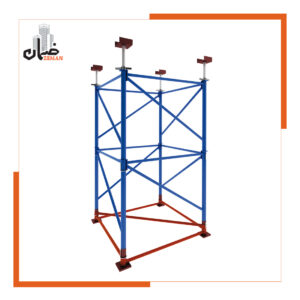

Formwork not only shapes the structure but also serves as temporary thermal insulation. In cold weather, formwork selection is strategic. Traditional timber formwork offers good insulation properties, while modular steel formwork provides high strength and dimensional accuracy, although its thermal conductivity requires preheating. For specific elements, circular, rectangular, square, curved wall, or prefabricated column forms may be used.

Formwork stability is ensured using connectors and support systems such as plumbing (alignment) jacks, which prevent deformation. For wall concreting, single-sided or double-sided formwork with lateral bracing (support jacks or walers) should be used to transfer lateral loads safely to the ground. Companies such as Zeman provide a wide range of products selected based on project size, climate, and budget. High-quality systems such as architectural wall formwork improve execution speed and thermal management.

Requirements During Concreting: Optimized Mix Design and the Role of Chemical Admixtures

After preparation, attention shifts to mix design and admixtures to ensure final quality. The main objectives are reducing freezable water and accelerating early-age strength gain.

Optimized Mix Design for Cold Weather

The water–cement ratio should be minimized to reduce free water. ABA recommends that without plasticizers, slump should not exceed 50 mm. Chemical admixtures such as plasticizers or superplasticizers (e.g., polycarboxylates) should be used to maintain workability without increasing water content, thereby accelerating early strength development. Type III (high-early-strength) cement, which releases more heat during hydration, is suitable, and increasing cement content accelerates setting. Pozzolanic or slag cements should be avoided due to their lower heat generation.

The Critical Role of Chemical Admixtures

Admixtures mitigate the adverse effects of low temperatures. Accelerators or antifreeze admixtures speed up setting so that water is consumed before freezing. Mechanisms include heat generation (exothermic reactions) or lowering the freezing point using compounds such as sodium nitrate or calcium chloride. Air-entraining admixtures create microscopic air bubbles that provide space for water expansion, reducing hydrostatic pressure and cracking, thereby improving durability under freeze–thaw cycles. Antifreeze admixtures are generally classified into two groups:

- Group One (weak electrolytes such as sodium nitrite), which lower the freezing point;

- Group Two (calcium chloride or calcium nitrite), which act as strong catalysts, improving cohesion, reducing cold joints, and significantly increasing compressive strength (sometimes multiple times at subzero temperatures).

Warning: Chloride-based admixtures are prohibited in reinforced concrete due to corrosion risk; dosage must be determined through laboratory testing.

The table below compares compressive strength of concrete with and without admixtures under cold conditions (based on Ratinov and Rosenberg):

| Temperature (°C) | Compressive Strength without Admixture (7 days, MPa) | Compressive Strength with Admixture (7 days, MPa) | Compressive Strength with Admixture (28 days, MPa) |

| –4 | 3.4 | 9.24 | – |

| –10 | 8.3 | 39.3 | 49.9 |

Curing and Protection: Ensuring Final Strength and Durability

After placement and vibration, the curing phase begins to protect concrete during its most vulnerable period. ACI emphasizes that concrete must be protected from freezing until it reaches a minimum compressive strength of 3.5 MPa (typically 48 hours at 10°C). Protection methods include insulation (polystyrene foam, thermal blankets, or polyethylene sheets), heating systems (hydronic heating or safe, CO-free heaters), and heated enclosures under extreme conditions.

The protection period follows ACI Table 7.2 (ranging from 2 to 6 days depending on loading). Temperature must be continuously monitored, and protection should be removed gradually to avoid thermal shock. Moist curing is permitted within enclosures, but excessive saturation should be avoided. For economic efficiency, a balance should be maintained between short-term acceleration and long-term durability.

Recommended ACI temperature limits for concrete placement based on section thickness:

| Section Thickness (mm) | Minimum Concrete Temperature at Mixing & Placement (°C) |

| ≥300 | 10 |

| 150–300 | 13 |

| 75–150 | 16 |

| <75 | 18 |

In conclusion, cold-weather concreting is feasible with proper planning, suitable materials, and adequate protection, and can result in high-quality concrete. In-situ testing methods such as maturity testing are recommended to verify strength development.

Principles and Methods of Winter Concrete Curing

After concrete placement, curing in cold weather is of critical importance. Unlike hot weather, where moisture retention is the primary goal, in cold conditions the most important objective is preventing heat loss and maintaining concrete temperature within an optimal range to complete hydration. Concrete must be protected against freezing until it reaches a minimum compressive strength of 5 MPa.

To achieve this goal, various methods are used:

- Thermal insulation coverings: This method involves covering fresh concrete with materials that prevent heat loss, such as thermal insulation blankets, polyethylene sheets, wet burlap, and polystyrene foam boards or EPS panels. Materials that absorb moisture, such as fiberglass, mineral wool, or straw, are not recommended because they may become saturated and lose their insulating properties.

- Heating systems: In large-scale projects or extremely low temperatures, active heating systems are essential. These include:

Industrial heaters: Gas or electric heaters are used to warm the environment around the concrete. Direct flame or smoke-producing devices must be avoided, as combustion gases may cause carbonation of the concrete surface and reduce strength.

Radiator or steam systems: In these methods, hot water or steam pipes are placed near the concrete surface to maintain the desired temperature through convective heat transfer. - Enclosures and creation of a protected microclimate: In high-rise structures and windy environments, enclosing the structure with tarpaulin or polyethylene sheets is an effective solution to prevent cold air and wind penetration. At this stage, metal scaffolding systems play a vital role. H-frame scaffolding and traditional scaffolding can serve as the primary structural support for installing protective coverings. However, more modular systems such as hammer scaffolding and cup-lock scaffolding are often more efficient due to their rapid assembly and dismantling. These scaffolding systems (e.g., cup-lock and service scaffolding) are not only used for worker access but also for creating a controlled and insulated environment. Companies such as Zeman, by offering a wide range of concrete formwork systems, triangular shoring (omega systems), and other solutions, enable the implementation of these advanced protective strategies.

Conclusion: A Comprehensive Outlook on Cold-Weather Concreting

Cold-weather concreting is a complex process with numerous potential risks, and successful execution requires a comprehensive and scientific approach. As discussed throughout this report, the primary challenges stem from the slowdown of the hydration process and the risk of water freezing during the early hours after placement—issues that can lead to permanent reductions in structural strength and durability.

To address these challenges, a systematic and multi-layered strategy is essential, following three key phases:

- Meticulous preparation: Including weather forecast evaluation, complete removal of snow and ice from the placement area, and preheating metallic surfaces such as reinforcement and formwork.

- Optimized mix design: By reducing the water-to-cement ratio, using rapid-hardening cements, and employing active admixtures such as concrete antifreeze agents and plasticizers.

- Active protection and curing: Through the use of insulating covers and heating systems to maintain concrete temperature over time. At this stage, scaffolding systems and support jacks play a critical role in creating protected environments and safely carrying imposed loads. Ultimately, successful cold-weather concreting is not a matter of chance, but the result of careful planning, engineering expertise, and the use of appropriate tools and equipment.

By offering a comprehensive range of execution solutions—including modular formwork systems, plywood and timber formwork beams, various modern scaffolding systems, and different types of slab and support jacks—Zeman Company stands as a reliable partner alongside engineers and contractors. This integrated, system-oriented approach ensures that construction projects meet the highest standards even under the most challenging climatic conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions About Cold-Weather Concreting

What exactly is considered cold weather for concreting?

According to the Iranian Concrete Code (ABA), cold weather refers to conditions where the average ambient temperature remains below 5°C for three consecutive days. Under such circumstances, special measures for concreting become mandatory.

What happens if concrete freezes?

Freezing of concrete during the early hours after placement can halt the hydration process and cause internal cracking due to water expansion (approximately 9%). This phenomenon may reduce the final strength of concrete by up to 50% and result in irreversible structural damage.

How can freeze-damaged concrete be identified?

The most common sign of freeze-damaged concrete is surface scaling and separation of surface layers under light pressure or impact. Additionally, hairline cracks may appear in thicker members, and over time the concrete may develop a powdery and brittle texture.

Is the use of open flames permitted for heating concrete?

No. Direct flame heating of fresh concrete can cause rapid surface drying and lead to shrinkage cracking. Furthermore, heating devices that produce smoke can cause surface carbonation of concrete and reduce its strength.

When can slab support jacks be removed?

The timing for removing under-slab support jacks depends on factors such as cement type, admixtures used, and ambient temperature. Generally, jacks should only be removed after the concrete has achieved sufficient strength to prevent deformation or collapse. In cold weather, this period is typically extended due to slower strength development.

What role does formwork play in cold-weather concreting?

In addition to shaping concrete, formwork acts as a thermal barrier that limits heat loss from fresh concrete. In cold conditions, using formwork with good insulating properties (such as timber or plywood) or preheating steel formwork before placement is essential.

Which admixtures are essential for cold-weather concreting?

Accelerating admixtures (concrete antifreeze agents) and plasticizers or superplasticizers are highly effective in cold weather. Accelerators speed up hydration and reduce the risk of freezing, while plasticizers enable a lower water-to-cement ratio. Air-entraining admixtures are also recommended for concrete exposed to freeze–thaw cycles.