What Is Reinforcement Work? | A Comprehensive Guide to the Execution of Reinforcement in Building Construction

Reinforcement, or rebar installation, as one of the most critical stages of construction, plays a fundamental role in ensuring the stability and durability of a structure. Reinforcement refers to the use of materials such as steel rebars or welded wire mesh placed within concrete to enhance its tensile strength and longevity. Concrete inherently demonstrates excellent compressive strength; however, it performs poorly under tensile stresses. The addition of reinforcement compensates for this weakness and enables concrete structures to withstand various loads and forces without cracking or collapse.

If you are seeking an in-depth understanding of reinforcement work, this article comprehensively examines all its aspects based on civil engineering principles. From basic definitions to execution stages, connection techniques, safety considerations, and even common mistakes, all topics are reviewed to enable effective application in your projects.

Reinforcement as a Critical Element in Concrete Structures

In modern construction practice, concrete is one of the most widely used building materials. This composite material has a distinctive engineering characteristic: extremely high compressive strength under axial loads, yet very limited and brittle tensile strength. Structural elements are continuously subjected to tensile forces. For example, in a concrete beam under load, the upper surface is in compression while the lower surface is in tension. If these tensile forces are not properly controlled, they will rapidly lead to cracking and ultimately result in sudden and catastrophic structural failure.

This is where steel complements concrete. The process of reinforcement involves placing a network of steel rebars within concrete in order to compensate for its tensile deficiency. These rebars carry all tensile and shear forces acting on the structure, while concrete primarily bears compressive loads. In fact, the combination of these two materials creates an artificial stone with ideal mechanical properties for construction, commonly referred to as Reinforced Concrete. Today, reinforced concrete is used throughout all structural components, from foundations to columns, beams, and slabs.

It is also worth noting the important distinction between rebar and reinforcement, which reflects the level of technical precision required in this profession. Rebar refers to raw, unshaped steel bars supplied directly from the mill, whereas reinforcement refers to rebars that have been cut and bent to the required shapes and are ready for placement within the structure. Reinforcement work refers to the process of connecting these prepared rebars using binding wire, mechanical fasteners, or approved cold-connection methods. Understanding this conceptual distinction is a fundamental step toward mastering professional reinforcement practices.

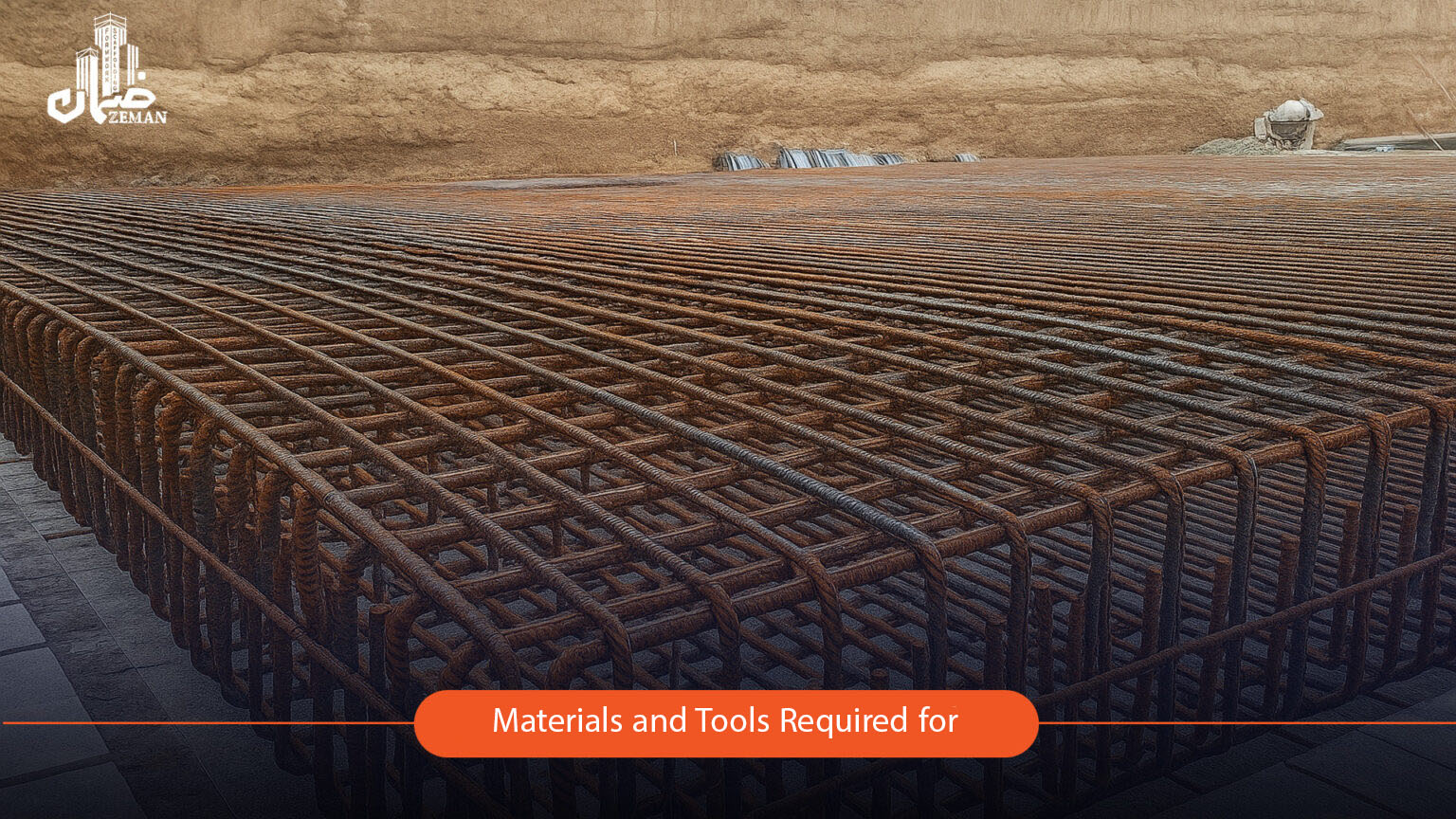

Materials and Tools Required for Reinforcement Work

To successfully execute reinforcement work, specific materials and tools are required. The primary materials include:

- Rebars: Plain (A1) and deformed rebars (A2, A3, A4) with different mechanical properties. For example, A3 rebars with a yield strength of 4000 kg/cm² are suitable for columns and beams, whereas A2 rebars are commonly used for stirrups.

- Binding wire: Typically black annealed steel wire is used for tying rebars.

- Spacers: Plastic or concrete spacers used to maintain the concrete cover, usually between 3 and 9 centimeters, in order to prevent corrosion.

- Stirrups (ties): Transverse rebars used to resist shear forces.

- Couplers: Mechanical connectors used for rebar splicing in large-scale projects.

The required tools include:

- Manual or electric rebar cutters.

- Manual or electric rebar bending machines.

- F-clamps and sledgehammers for rebar alignment and adjustment.

- Wire brushes or sandblasting equipment for cleaning rebars from rust (surface rust is acceptable as long as it does not reduce the bar diameter by more than 0.5 mm).

From Rebar to Reinforcement: Understanding Materials and Standards

Reinforcement work is a process in which steel rebars (commonly referred to as reinforcement) are cut and bent in accordance with structural drawings and then connected using binding wire or other approved methods. This steel framework is embedded within concrete to compensate for its weakness in tension. While concrete inherently has high compressive strength, it performs poorly under tensile and shear forces; the ratio of tensile to compressive strength is approximately 1:10. By adding reinforcement, concrete becomes “reinforced concrete,” capable of resisting axial, shear, flexural, and torsional forces.

Rebars are typically manufactured through hot-rolling or cold-rolling processes and are supplied either as straight bars (usually 12 meters in length) or in coil form. According to Part 9 of Iran’s National Building Regulations, reinforcing steel is classified into hot-rolled rebars and cold-drawn wires. Reinforcement work not only increases tensile strength but also enhances energy absorption, structural ductility, and crack control. In large-scale projects such as bridges, tunnels, and high-rise buildings, this process represents the most fundamental step in ensuring structural safety.

Selecting and procuring the appropriate rebar is the first and most critical step in proper reinforcement execution. This selection must strictly comply with structural drawings and engineering standards. In Iran, ISIRI 3132 is recognized as the primary national standard for rebar production and classification, dividing rebars into four main categories. Understanding the characteristics of each category is essential for correct application:

- Plain Rebar A1 (S240): This type has a smooth surface without ribs. With strength grade S240, it has the lowest tensile strength and the highest ductility among construction rebars, making it suitable for welding and fabrication. Its primary application is spiral reinforcement in piles and circular columns.

- Deformed Rebar A2 (S340): Featuring spiral ribs on its surface, A2 rebar is classified as semi-hard and has higher tensile strength than A1. Due to its relative flexibility, it is well suited for stirrups and ties that require bending.

- Deformed Rebar A3 (S400): This is the most commonly used type in the construction industry. Its ribs are arranged in a herringbone pattern along the bar. A3 rebar is classified as hard and relatively brittle; welding is not permitted, and it offers limited resistance to sharp bends. It is mainly used for longitudinal reinforcement in beams, columns, and foundations.

- Deformed Rebar A4 (S500): A4 rebar features complex compound ribs and provides very high tensile strength. It is also classified as hard and is primarily used in heavy-duty and sensitive projects. With advances in production technology, some variants achieve adequate ductility despite their high strength and may allow conditional welding.

The selection of rebar type should not be based solely on price or availability; rather, it depends on structural design, applied loads, and environmental conditions. An error at this stage can jeopardize the performance of the entire structure. For any construction project, preparing a reinforcement schedule or bar bending schedule based on drawings is essential. This schedule includes detailed information such as location, size, shape, bending details, and quantity of rebars, providing precise guidance for the reinforcement process.

| Rebar Type | Strength Grade | Surface Pattern | Yield Strength (MPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Ductility | Weldability | Main Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | S240 | Plain (Smooth) | ≥ 240 | ≥ 360 | Very Ductile | High | Spirals, light stirrups, non-structural connections |

| A2 | S340 | Spiral ribbed | ≥ 340 | ≥ 500 | Semi-hard | Moderate | Stirrups, ties, shrinkage and temperature reinforcement |

| A3 | S400 | Herringbone ribbed | ≥ 400 | ≥ 600 | Hard | Low (Not permitted) | Longitudinal reinforcement in beams and columns |

| A4 | S500 | Compound ribbed | ≥ 500 | ≥ 650 | Hard | Conditional / With caution | Heavy-duty and critical projects |

Step-by-Step Reinforcement Execution Process

Reinforcement execution consists of a series of precise and interdependent steps, each of which must be carried out with the highest level of accuracy.

1. Planning and Drawing Review

Before any execution begins, site engineers and supervisors must thoroughly review structural drawings and bar bending schedules to determine the exact location, dimensions, and specifications of each rebar. This stage is conducted under the supervision of the design engineer and inspector, and any ambiguities must be resolved before work commences.

2. Cutting and Bending of Rebars

After determining the required specifications, rebars must be cut and bent to the specified lengths and shapes. In order to preserve the mechanical properties of steel, cold cutting methods are preferred over hot cutting techniques. Cold cutting tools include various types of rebar shears, guillotines, band saws, and waterjet cutting systems. The use of hot cutting tools such as oxy-fuel cutting or plasma cutting is strongly discouraged, as excessive heat can alter the steel’s mechanical properties, making it brittle and prone to cracking.

Rebar bending must also be carried out carefully using appropriate bending machines or manual bending levers. One of the key considerations at this stage is avoiding rebar bending at temperatures below 5°C, as steel becomes more brittle under such conditions and may develop cracks at the bend locations.

3. Rebar Tying and Splicing

After cutting and bending, the rebars are arranged in a grid or cage configuration and connected together. This process is performed using reinforcement binding wire (typically soft annealed steel wire with a diameter of 1.5 to 2 mm) and pliers or automatic tying machines. Tying is not required at every intersection unless the spacing between rebars is less than 30 centimeters, in which case alternate intersections may be tied.

The purpose of tying is solely to hold the rebars firmly in place and does not contribute to the structural strength of the member. The importance of this phase lies in preventing rebar displacement during concrete placement, which is a high-pressure and vibration-intensive operation. Any movement of rebars can reduce the concrete cover, leaving the reinforcement exposed to corrosion.

When the available length of rebars is insufficient for a structural element, rebar splicing is required. The most common method is the lap splice or overlap, in which two rebars are placed alongside each other over a specified length and tied together with binding wire. The lap length must comply with national standards and design requirements (typically 55 times the bar diameter or at least 30 centimeters) to ensure proper force transfer. More advanced methods include mechanical splicing using couplers and welded splicing (forging).

4. Installation and Placement

Finally, the reinforcement cage is positioned in its designated location. At this stage, the use of spacers to ensure the required concrete cover is essential. Concrete cover is the distance between the outer surface of the rebar and the formwork surface, providing protection against corrosion, moisture, and environmental effects. The thickness of the concrete cover varies depending on the structural element: for foundations in direct contact with soil and moisture, a minimum of 7.5 cm is required, while for other elements, it generally ranges from 2.5 to 5 cm.

Reinforcement in Main Structural Components

Reinforcement details and requirements vary in each part of a structure depending on the type and magnitude of applied loads.

1. Foundation Reinforcement

The foundation, as the base of the building, transfers all structural loads to the ground. Foundation reinforcement starts after excavation and placement of lean concrete (blinding concrete) and consists of two main reinforcement meshes: a bottom mesh and a top mesh, separated by spacer bars or chairs (rebar chairs). In addition, starter bars extending from the foundation are installed to connect the foundation to the columns of the first floor. The length and bending details of these starter bars must be carefully calculated to ensure proper load transfer.

2. Column and Wall Reinforcement

Columns and shear walls are primarily compression members, but they also resist lateral forces such as those induced by earthquakes. Column reinforcement consists of longitudinal rebars (for resisting axial and bending forces) and transverse reinforcement (commonly referred to as ties or stirrups). These ties confine the concrete core and provide resistance against shear forces.

One of the most critical aspects of column reinforcement is splicing longitudinal rebars. Splices must not be concentrated at a single level, as this would create a weak plane within the column. Additionally, when connecting new columns to an existing structure or strengthening existing columns, post-installed rebars using chemical anchoring systems are employed. In this method, rebars are placed into drilled holes in the concrete and bonded using epoxy-based adhesives. To avoid irreversible errors, every step of this process, from drilling to adhesive injection, must be executed with high precision.

For shear walls, and particularly for curved wall formwork, reinforcement and formwork must be performed in close coordination. Arched or specially designed modular steel formwork systems are used to construct circular walls, such as those found in silos and water tanks.

3. Slab Reinforcement

Slab reinforcement varies depending on the slab system used, such as joist-and-block slabs, solid slabs, waffle slabs, and others. In reinforced concrete slabs, in addition to the main reinforcement, temperature and shrinkage reinforcement is provided to prevent cracking caused by concrete shrinkage and thermal variations. These rebars must be fully surrounded by adequate concrete cover; if they are placed inside polystyrene blocks or come into direct contact with them, their effectiveness is lost and cracking may occur. Another critical type of reinforcement in slabs is negative moment reinforcement, which is placed at the top of supports to resist negative bending moments.

Synergy Between Reinforcement, Formwork, and Scaffolding

Reinforcement work does not function in isolation; it is an integral part of a unified construction system that works in full coordination with formwork and scaffolding. Understanding this synergy is essential for every construction professional.

1. The Role of Formwork in Reinforcement

Formwork is a temporary structure that contains freshly placed concrete until it hardens and achieves its intended shape. This process is closely linked to reinforcement work. In the case of columns, reinforcement is completed first, and then formwork systems such as rectangular column formwork, square column formwork, or circular column formwork are installed around it. This logical sequence is essential because once the formwork is installed, access for placing and tying reinforcement becomes difficult or even impossible.

To ensure proper alignment of formwork and reinforcement, tools such as plumbing jacks and wall bracing systems are used. Additionally, formwork joints must be carefully sealed with gypsum mortar to prevent cement slurry leakage. For special structures such as tunnels, dedicated systems such as tunnel formwork are employed, which require precise coordination with the corresponding reinforcement layout.

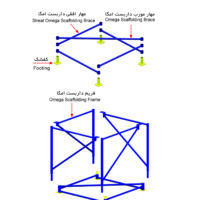

2. The Role of Scaffolding and Shoring

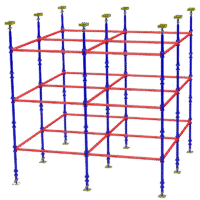

After slab reinforcement and formwork installation, a temporary support system is required to carry the weight of freshly poured concrete and prevent slab collapse. This system is known as scaffolding or shoring. Traditional tube-and-coupler scaffolding has long been used; however, modern systems such as H-frame scaffolding and hammer-head (cup-lock) scaffolding have become increasingly popular due to faster installation and higher safety levels. A specific type of cup-lock scaffolding, known as cup-lock rosette scaffolding, is frequently used in heavy structures due to its superior stability and load-bearing capacity.

In large-scale and high-rise projects, triangular shoring systems and various types of slab jacks and support jacks are used to bear heavy loads and allow precise height adjustments.

Purchasing standard slab jacks, U-head slab jacks, and various wall and column support jacks at this stage plays a vital role in ensuring structural safety and stability. In addition, the use of appropriate scaffold planks on scaffolding systems provides safe access and improved working conditions for workers.

Common Mistakes and Quality Control in Reinforcement Work

Even a single overlooked detail in reinforcement work can lead to serious structural damage. Identifying common mistakes is the first step toward preventing them.

1. Common Execution Errors

- Insufficient concrete cover: Failure to use spacers causes rebars to touch the formwork, exposing them to air and moisture, which leads to corrosion and reduced reinforcement strength.

- Inadequate lap length: If the overlap length at splices is less than the required standard, force transfer is compromised, and the splice location becomes a structural weak point. This error is often committed to reduce material waste.

- Improper use of rebars: Using rebars in unsuitable applications (e.g., A3 rebars in sharp bends) can result in bar fracture.

- Contaminated rebars: The presence of rust, paint, oil, or any surface contamination reduces bond strength between steel and concrete and adversely affects structural performance.

- Improper hook detailing: The absence of proper 90° or 135° hooks at the ends of beam longitudinal reinforcement at column connections can significantly reduce flexural capacity and cause failure at these locations.

- Incorrect placement of temperature reinforcement: Placing temperature rebars inside polystyrene blocks or allowing them to adhere to blocks renders them ineffective and leads to thermal cracking in slabs.

2. Quality Control and Inspection

All reinforcement work stages must be carefully inspected by the supervising engineer prior to concrete placement. A comprehensive inspection should include the following:

- Dimensional and quantity checks: Verification of rebar size, quantity, and placement according to construction drawings.

- Inspection of bends and splices: Verification of lap lengths, correct splice locations, and proper hook execution.

- Concrete cover control: Ensuring the presence of spacers and compliance with required concrete cover thickness.

- Tie inspection: Ensuring ties are secure and rebars are properly immobilized.

- Cleanliness inspection: Confirming that rebars are free from any surface contamination.

Conclusion: Why Reinforcement Is the Foundation of Successful Concrete Structures

Reinforcement work is not merely a technical step; it is the cornerstone of safety and performance in concrete structures. By adhering to engineering principles, using high-quality materials, and applying rigorous supervision, durable and resilient structures can be achieved. If your projects require reinforcement work, consulting experienced professionals and complying with national standards is essential.

Reinforcement is a complex and highly technical process that forms the structural backbone of reinforced concrete construction. From selecting appropriate rebars and complying with national standards to executing precise cutting, bending, and tying operations, every stage is critical. This process is intrinsically linked with formwork and scaffolding systems in an integrated operational cycle to ensure the final stability and safety of the structure. Any negligence at these stages can result in irreversible and catastrophic consequences.

Therefore, utilizing up-to-date technical knowledge and high-quality equipment—including concrete formwork systems, modular steel formwork, cup-lock scaffolding, and various slab and support jacks—is not merely a competitive advantage, but a professional necessity in the construction industry. Zeman Co., by offering comprehensive solutions and standard-compliant equipment, stands alongside you throughout all these stages to ensure your projects reach completion with the highest levels of quality and safety.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How long does reinforcement work take?

The duration of reinforcement work depends entirely on the scale and complexity of the project. Reinforcing the foundation of a small building may take only a few days, whereas in large multi-story projects, this process can extend over several weeks or even months.

2. Why is A3 rebar not suitable for sharp bending?

A3 rebars feature herringbone ribs and are classified as hard reinforcement steel. This hardness results in relative brittleness under sharp bending angles, increasing the risk of cracking or fracture. For such applications, more ductile rebars such as A2 are recommended.

3. What causes the price difference between standard slab jacks and U-head slab jacks?

Standard slab jacks are generally less expensive than U-head slab jacks, which are equipped with U-shaped heads. U-head jacks are specifically designed to support and secure various beams and formwork systems, including plywood panels and timber or H20 timber beams. Their enhanced functionality and load distribution capabilities directly influence their higher price.

4. Why is the use of plumbing jacks and wall/column support jacks essential?

The use of plumbing jacks and wall/column support jacks is essential to maintain vertical alignment and stability of elements such as columns and walls during concrete placement. These tools prevent formwork displacement due to fresh concrete pressure, significantly improving execution accuracy, structural integrity, and overall safety.

5. What are the applications of scaffold planks and traditional scaffolding?

Scaffold planks and traditional scaffolding are commonly used in small-scale and low-rise projects where sophisticated modular systems are not required. Despite their longer installation time, their simplicity and lower cost make them a viable option in certain construction applications.

6. Is it permissible to connect rebars using conventional welding?

According to national building regulations and engineering standards, conventional welding is not permitted for connecting rebars, as excessive heat can alter the steel’s properties and reduce its strength. Approved methods include lap splicing, and in specific cases, cold welding (forging) or mechanical splicing using couplers.